There Is No Substitute for Free Trade and Deregulated Markets

Trump’s vaunted bargaining skills are no substitute for fixed rules and low tariffs.

One striking feature of the endless disputes over Trump’s tariff crusade is the lineup of his political detractors and supporters. The former group, of course, includes the long list of Biden and Harris officials who, like Rahm Emanuel, sound even more pro-free trade now than they did when Biden was president, where equivocation was the norm. The wipeout of $11 trillion in financial assets can focus the mind.

The left’s strongest arguments come from their willingness to adopt the classical liberal arguments, long urged by such stalwarts as Douglas Irwin, Phillip Magness, and Phil Gramm & Donald Boudreaux. This group holds that gain is maximized by reducing tariffs and all other barriers to trade. The ideal is to make international borders irrelevant so that a set of ruinous and discriminatory taxes does not lead to the inefficient substitute of domestic for foreign production when the latter has a bona fide market advantage. Low tariffs lead to higher levels of domestic consumption and greater success in export markets, as the cheaper inputs lead to lower export prices. I am uneasy about using tariffs to retaliate against nations that impose such tariffs on us or subsidize their production. Why gum up international markets with additional restrictions? Indeed, Trump appeared to agree when he exempted phones, computers, and chips from the new tariffs, including from China, without reciprocal concession. Sadly, however, he did it in the worst way, ad hoc and selectively, for some industries but not others. In addition, why not let foreigners subsidize us, so that even direct competitors can adjust their mix of goods and services to take advantage of the subsidized goods and services?

We have seen the wreckage of adopting the contrary position of starting a unilateral trade war that no one can win. There are so many stories, including the haul of on-target criticisms from the rightly panicky front page of the Weekend Edition of the Wall Street Journal (here, here, and here) that highlight major disruptions with worse to come—recessions included—if Trump does not change course and soon. But don’t hold your breath because even his recent pause in the tariff war did not remove the all-purpose 10 percent tariff in place.

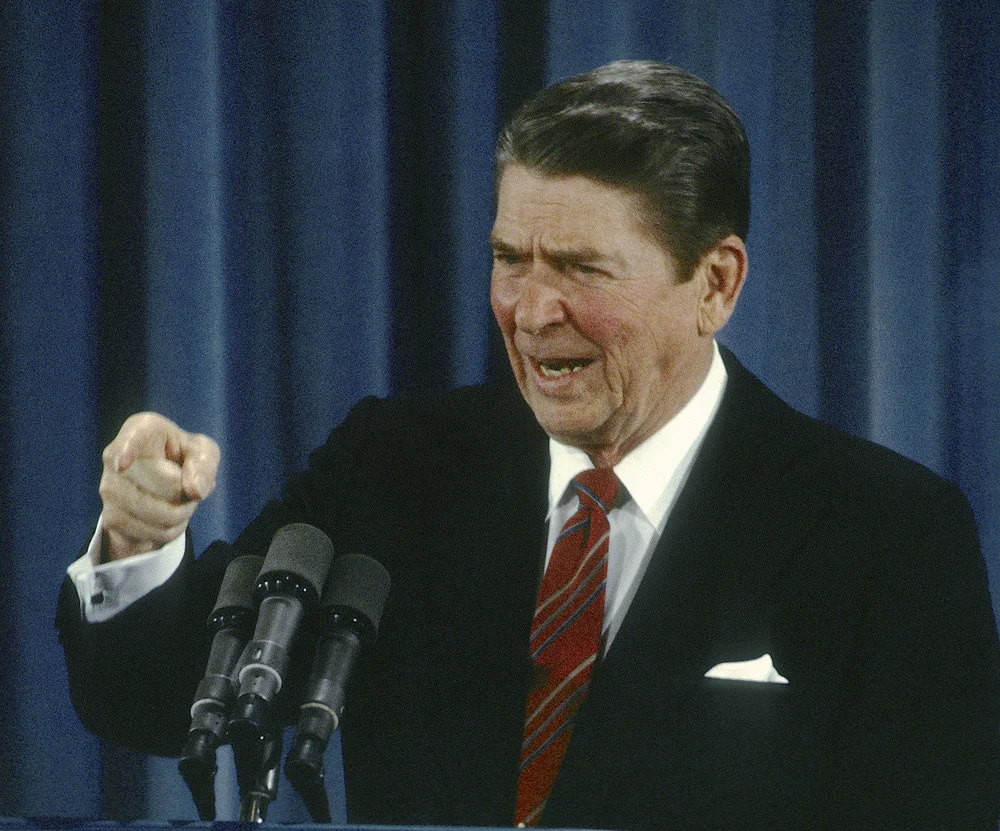

But far from heeding the warnings, what we hear from Trump (when he is not handing out exemptions) is the precise opposite —“hang tough” in the short run and historic gains will come in the long run, even if they won’t come easily. To keep people hanging tough, Trump relies on a lineup of public defenders to counteract the ever sharper criticism. Thus, one Trump supporter, Victor Davis Hanson, offers a strongly worded denunciation of all things Biden, including the unhappy state of trade and business relations before Trump:

There is so far no alternate agenda on trade deficits, budget deficits, and debt. That is, no one on the left—or, for that matter, the libertarian right or the now inert Republican establishment—can outline an alternate pathway to Trump’s remedies for America’s dire problems.

Not so. A strong libertarian agenda thinks that the best approach to this sad state of affairs is a systematic program of deregulation to undo the legion of prior mistakes that Biden’s minions either instituted or supported on such matters as using exaggerated estimates of environmental harms to stifle pipeline construction, imposing EV mandates on the states, turning securities disclosure laws into a clumsy tool to monitor carbon dioxide levels on a firm-by-firm basis, and much more. Deregulation reduces administrative costs and opens up markets, a double savings that leads to higher social benefits no matter what happens to tariffs. Make the country more receptive to domestic investment, and you make it more attractive to foreign investments, which will start undoing Hanson’s dire problems, assuming we know what they are. Yet, here Trump and company get matters wrong when they think that a defunct manufacturing sector needs a massive infusion of new jobs, when the unemployment rates are low today, so that confrontational tariffs are far inferior to opening up domestic markets to business at both the state and federal level. Trump’s tariff rollercoaster sends the wrong message—stay out because you have no idea what the next round of tariffs and taxes will do to your long-term business. Trump is wedded to his America First Investment Policy for “welcoming foreign investment” of which tariffs were no part. So, why this sour greeting?

The answer that comes from Trump’s supporters is loud and clear. Larry Kudlow insists that everyone favors a world with zero tariffs, only to insist that the way to get to domestic nirvana is to allow that master negotiator, Donald Trump, to achieve that goal. After all, now close to 70 nations are lining up outside the Trump administration’s doors, hankering for deals, which Trump hopes to churn out in the next three months. How then can prosperity be far behind?

Easy.

The key point here is that the new pattern of negotiation of these supplicants is perfectly rational—conditional on having Trump’s tariff policy in place. The status quo is a dead loser for everyone, but there is no way any of America’s trading partners can return to the status quo unilaterally. So, they have only one way to break the logjam: to steel themselves to deal with Trump and his tariff barriers. But what kind of concession can we expect and what kind of time-table? The answer relates to standard bargaining theory, which notes that the ideal solution is to have high rates of transactions at low transaction costs, which is yet another implication of the work of Ronald Coase that shows that controlling these costs is the best way that any government can move in that direction. One needs the rapid-fire transactions of a modern exchange, not the cumbrous tit-for-tat bargaining of dealing with multiple issues and multiple parties in real time, well knowing that holdouts will block the path in many cases to total tariff relief in both directions. Matters are still worse because it is highly likely that we shall not get close to that ideal position even if, as Arthur Laffer and Stephen Moore urge, this solution is first best, given that Donald Trump is so good at wheeling and dealing he could even win a Nobel Peace Prize. Indeed, that nirvana might have had a remote chance of success had it been offered with conditions before “liberation day” sparked the current meltdown.

It won’t happen. The existential problem here is that it takes two to tango, and nothing says that most nations think that they will be better off with this deal than with some other unique agreement that they will be able to negotiate for themselves. At this point, we can expect delays, which will be compounded because the deals that each nation will accept with the United States will fluctuate depending on how matters move. So, let us assume that Trump is a phenomenal negotiator. That means that if world GDP or trade plummets by, say, 15 percent, Trump will ensure that his trading partners will be even worse off than the United States.

There are good reasons to expect such dire results, commonly occurring whenever parties are allowed to negotiate deals where each trapped party has no place to go. Thus, as early as 1856, the United States Supreme Court in Post v. Jones set aside a sham auction when a ship stranded at sea sold its cargo of whale oil to nearby ships far below market prices. As with all contracts, this agreement left both sides better off, but the Court nonetheless struck down the deal because of the abuse of monopoly power and reduced the salvor to only a reasonable fee, a practice uniformly followed in response to other necessities on land or at sea.

Unfortunately, public law often tends to veer sharply in the opposite direction, including the common state cartel arrangements started, as in California grapes, in the New Deal and then used under the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 to put the government’s monopoly behind labor unions’ collective bargaining negotiations. Yet, when these negotiations break down, as they often can, strikes or lockouts follow, making both sides losers while further disrupting essential services, especially transportation services and perishable goods, neither of which can be stored. All too often, these breakdowns can result in the bankruptcy of a firm that is saddled with an onerous labor contract, which happened when the US trucking firm, Yellow, was forced into bankruptcy after a prolonged siege from the Teamsters union, which, of course, denies any causal role. What is needed in these situations is a removal of the collective bargaining system, which does no good for overall output, even when the immediate parties have reached a settlement that leads to monopoly wages. So the analysis ends where it begins—remove anticompetitive features in the domestic market, and both local and foreign firms can thrive. The more Trump emphasizes his superior bargaining skills, the longer the country and the world will face a steady increase in economic insecurity and a steady decline in public welfare from his sublime bargaining tactics.

Richard A. Epstein is a senior research fellow at the Civitas Institute. He is also the inaugural Laurence A. Tisch Professor of Law at NYU School of Law, where he serves as a Director of the Classical Liberal Institute, which he helped found in 2013.

Economic Dynamism

The American Dream Is Not a Coin Flip, and Wages Have Not Stagnated

This paper challenges the prevailing narrative that stagnant wages are causing the American dream to fade. It contrasts subjective public opinion with revised objective intergenerational mobility measures.

Political Economy and the Rise of Commercial Humanism

Western attitudes toward commerce have transformed from early moral condemnation to a modern appreciation that sees trade as socially beneficial.

.webp)

A Bad Business on the Bayou

Chevron finds itself the victim of a political alliance between the tort bar and Louisiana Republicans.

.webp)

Congress Must Shield US Companies from European Regulations

Congress should exercise its constitutional powers over foreign commerce to guard American companies against overregulation by the European Union.

How Tariffs Starve U.S. Investment

The incentives created by Trump’s misguided tariff gamble will ultimately discourage investment in America.

American Aspiration: Our Anti-Dynamism Problem

Dynamism requires agency, creativity, risk tolerance, and sometimes a simple desire for adventure.

.png)

_(7184104335).webp)

.webp)

.webp)