Trump's Tariff Fundamentalism

His economic delusions are producing economic disasters at home and abroad.

In this past week, the Trump round of tariffs has taken its toll on the pockets of every person and organization in the United States, including his political base. Since “liberation day,” — his term, surely not mine — April 2, 2025, President Trump tells us that we should “hang tough” even though “the U.S. stock market plummeted, with the Dow Jones industrial average losing 9.2%, the S&P 500 falling 10.5% and the tech-heavy Nasdaq tumbling 11.4%.” European and Asian markets have also suffered. And mid-Monday the sell-off continues. Those disastrous results are consistent with every argument made by Trump boo-birds who, like me, are so simple-minded that they conclude that Trump is too clever by half, so that his stubborn determination to go the distance ensures that this string of losses will continue unabated until his political support, already crumbling in the face of mass protests, collapses.

The arguments against the Trump tariffs are legion. First, any tax reduces potential gains from trade. Those losses are increased when they fall unequally on two competitive firms or individuals. Unlike a uniform tax, selective taxes distort relative prices, which then reduces total output as inefficient modes of production will displace firms with superior techniques. Worse still, a tax with constant impact across all firms, both domestic and foreign, will not generate any kind of reprisal that can lead to the type of trade war that the jingoist Trump—the ALL CAPS are his— now celebrates with the promise that

We are bringing back jobs and businesses like never before. Already, more than FIVE TRILLION DOLLARS OF INVESTMENT, and rising fast! THIS IS AN ECONOMIC REVOLUTION, AND WE WILL WIN. HANG TOUGH, it won’t be easy, but the end result will be historic.

But how can that be? The stock market provides an early glimpse of what the future will hold, as tomorrow’s anticipated outcomes are reflected in the current value of shares. The collective predictions of investors and traders has no reason to paint an unduly pessimistic view of market prospects. What they offer is a collective unbiased estimate of future production, and they do not credit the Trump prediction of a domestic renaissance spurred by the arrival of foreign investment capital. But what magic can he conjure up to wish away the $2.5 trillion loss from the S&P on Thursday alone? Trump, of course, offers no timetable or guarantee to his $5 trillion bonanza, which, ironically, hardly makes a dent in the total financial losses already incurred.

Of course, there may be some plusses, for example, a move by foreign companies to build more vehicles inside the United States to get around the tariff wall. But these actions take time, and the constant instability in the marketplace—just how long will these tariffs last anyhow?—will dampen those gains. Alternatively, what if tariffs raise prices? “I couldn’t care less,” Trump said. “I hope they raise their prices, because if they do, people are gonna buy American-made cars. We have plenty.” Really? If imports are close to half the total? In addition, the parts for cars made in America often come in from overseas, and these higher tariff costs have to be passed on to customers at least in part in order for these firms to survive, even if buyers do compromise, say, by buying cheaper models. To top off his economic ignorance, Trump issued yet another threat, stating that companies would face unspecified consequences if they raised prices in response to market forces, even if those price increases were necessary to avert bankruptcy. To address that concern, Trump is right to say that American manufacturers should be grateful for the removal of numerous electric car mandates, but it is beside the point. There is no reason why the benefits from a sensibly deregulatory regime must be frittered away by a de facto price control system that will result, if implemented, in long queues and devious strategies similar to those that emerged in the 1970s under Richard Nixon’s ill-fated scheme to cap gasoline prices.

So why this strategy? To answer that, we must look to the Trump apologists, who seem to the think that a miraculous long-term turnaround will vindicate his strategy. The economist–turned–Trump apologist Lawrence Kudlow views this move as a reversal of a long-term approach where our trading partners will no longer be allowed to eat our lunch going forward. In his recent op-ed for The Sun, he writes:

With Trump’s Tariffs, the Misbehaved Children Are Coming Home to Papa: Trump’s breakthrough on lowering trade barriers with Vietnam is the latest evidence that he is a master negotiator.

He then adds: "Since 1997, America has lost 5 million manufacturing jobs and shuttered 90,000 factories. This has got to stop. And Mr. Trump is the guy to stop it."

Take the points in order. What exactly do we gain from a deal with Vietnam that offsets the trillions in short-term losses? And why was it impossible to conduct trade negotiations without the threat of global warfare? And who says that these deals worldwide will come fast enough and sensibly enough to offset the losses that are likely to continue as many major players are arming for a trade war that no one can win? And for understanding the global economy, these one-off bilateral contracts will, as the economist Douglas Irwin reminds us, lead to further destabilization by requiring perhaps some 2.6 million nation-specific tariffs. Even these rates, however, could not be set just once but would require frequent readjustment if one of our trading partners or the US makes a bilateral deal with some third party that requires further adjustments across the board.

And next, just what does it mean to bring back manufacturing jobs as an economic panacea? A lot has happened since 1997 that helps explain why manufacturing productivity can go up with fewer workers. Automation and improved management techniques allow United States businesses to produce more with less. Even before the latest round of tariffs, the sector had already experienced strong innovation and growth. Firms owe fiduciary duties to maximize profits for shareholders, not wages for workers, who gain higher wages and better benefits from higher productivity, not union contracts. Other nations may have lower cost structures, so American firms might well find it easier to deal with high-tech service industries for which its workforce is more suited. No one quite knows whether the death of any given old firm is a good or bad thing, but painting by the numbers is the worst way to make policy.

What is needed is not a master policy but decentralized choices where individual firms can make their own investment deals, just as they do in domestic markets where states and localities can compete for deals. It is far better to stabilize public infrastructure, but that will be harder to do the longer Trump’s erratic policies drown out saner voices on international trade. But any long-term gain in this ten-percent sector could not compensate more than a tiny fraction of the losses incurred on April 3 and 4, even if this form of quasi-industrial policy could generate any systematic gains at all.

So, if the economics fail, what's next? One recent effort to rehabilitate Trump on noneconomic grounds has been offered by David Frost, the chief negotiator for Brexit, who concludes that “there’s method to Trump’s tariff madness.” That method makes sense, he argues, because all right-minded people understand that the political dimension in both domestic and international affairs should warn against being “free market purists.” It is right, of course, to think in terms of comprehensive policy, but there is no reason, a priori, that Frost’s wider list of considerations calls for any reversal of policy. People who get the economics wrong also often misunderstand the collateral issues. Thus, why should anyone think that our economy has been “hollowed out” by the Chinese influx of cheap imports?

These imports improve the lot of those who consume them and may provide inputs that allow American firms to make better goods for both domestic consumption and the export market. Nor is there any reason to think that an “America First” policy makes sense in its own terms, especially if it leads to the kinds of selfish behaviors that alienate our allies and embolden our enemies. Indeed, tying the loss of American jobs to the predations of our neighbors often uses scapegoats to explain many failures that lie closer to home. It is often a delusion to think that the jobs that went overseas would remain just where they started. The more likely prospect is that, given the economic pressures, they would relocate to more receptive locations in the United States or disappear altogether. The massive movement of employees from economic backwaters like New York and California to dynamic places like Texas, Florida, Tenneessee, and South Carolina has nothing to do with China, and the concerted political effort to keep jobs in place reduces much-needed incentives for market liberalization in places with high taxes and strong union control. Sady, the fault too often lies in ourselves and not our stars. Bad economics and bad politics often stem from the same misguided view that we need more regulation. Trump’s follies of the last tragic days prove the opposite.

Richard A. Epstein is a senior research fellow at the Civitas Institute. He is also the inaugural Laurence A. Tisch Professor of Law at NYU School of Law, where he serves as a Director of the Classical Liberal Institute, which he helped found in 2013. He has served as the Peter and Kirstin Bedford Senior Fellow (adjunct) at the Hoover Institution since 2000. Epstein is also the James Parker Hall Distinguished Service Professor of Law Emeritus and a senior lecturer at the University of Chicago.

Economic Dynamism

The American Dream Is Not a Coin Flip, and Wages Have Not Stagnated

This paper challenges the prevailing narrative that stagnant wages are causing the American dream to fade. It contrasts subjective public opinion with revised objective intergenerational mobility measures.

Political Economy and the Rise of Commercial Humanism

Western attitudes toward commerce have transformed from early moral condemnation to a modern appreciation that sees trade as socially beneficial.

.webp)

A Bad Business on the Bayou

Chevron finds itself the victim of a political alliance between the tort bar and Louisiana Republicans.

.webp)

Congress Must Shield US Companies from European Regulations

Congress should exercise its constitutional powers over foreign commerce to guard American companies against overregulation by the European Union.

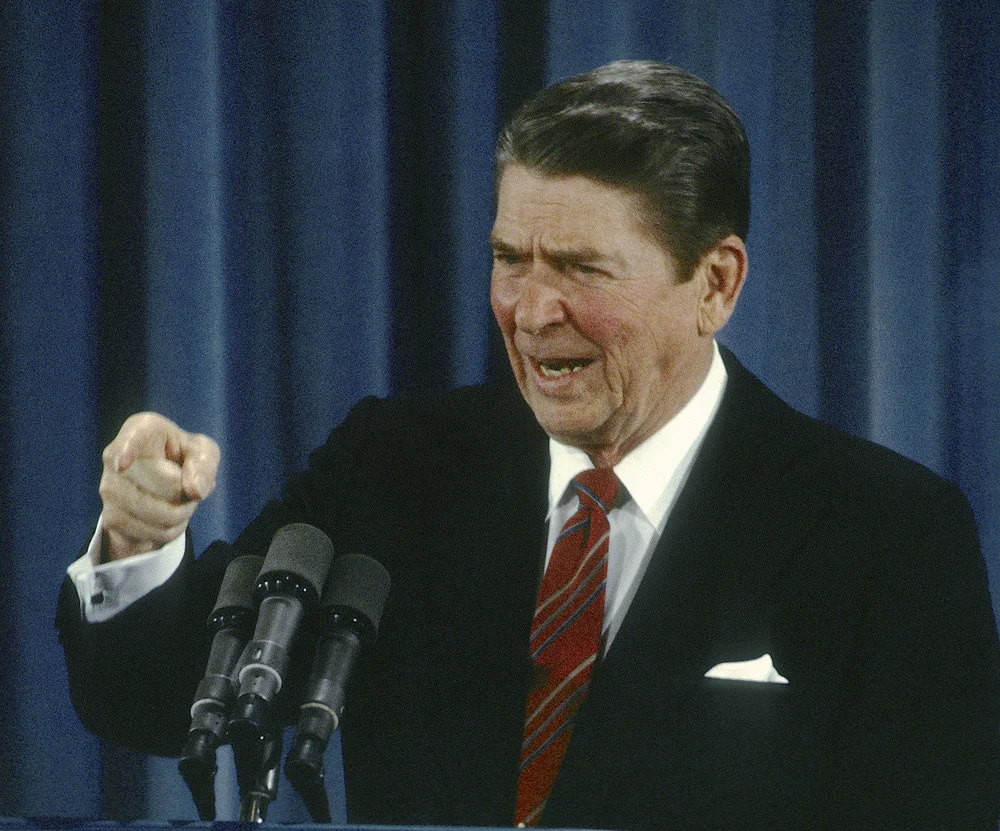

Trade Protection and Tariffs from Reagan to Trump

Donald Trump's enthusiastic embrace of tariffs and protection for American industry appears to be a complete reversal of Reagan and Reagan-era policy.

Transatlantic Trade War Produces No Winners

The EU should end its competition policy vendetta. Trump should drop his tariffs.

.png)

_(7184104335).webp)

.webp)

.webp)

.webp)