How Tariffs Starve U.S. Investment

Trump's tariff reciprocity will encourage foreigners to reduce their trade deficits with the U.S. rather than focusing solely on reducing tariffs themselves.

While President Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs are now paused for 90 days, with separate tariffs on China, Canada, and Mexico presumably remaining in place, the U.S. still has the highest tariff rates in over a century. But what should Trump do after this latest surprise pause? Based on evidence from the stock and bond markets, he should eliminate these tariffs altogether and pivot to tried-and-true methods: lowering taxes and deregulation.

Why Not Tariffs?

Intended to boost the consumption of American-made goods and spur domestic investment, tariffs are a case study of how noble aims can falter under misaligned incentives. Touted as a pathway to economic sovereignty, history reveals that these tariffs are much more likely to burden domestic producers and consumers, alienate foreign partners, and undermine the very goals they seek to achieve.

However, these specific “Liberation Day” tariffs will have much broader effects, especially those tied to capital flows, revealing a deeper design flaw. We’re thankful that President Trump paused them because it gives us time to discuss how their reimplementation will distort incentives. Because of how they have been implemented, Trump's tariff reciprocity will encourage foreigners to change their trading patterns with the U.S. rather than focusing solely on reducing tariffs. This has concerning implications.

First, the White House hopes these tariffs will prod foreigners to buy more American goods and services, increasing our exports and narrowing our trade deficit. This is a fantasy. The simple fact is that we are significantly wealthier on a per-capita basis than most of our trading partners. Foreign countries export their products to the U.S. precisely because their populations often cannot afford the goods they produce. Expecting them to suddenly find the wealth necessary to purchase our output, especially as its price rises thanks to the tariffs, ignores this stark economic reality. The accompanying decrease in U.S. imports, by making the dollar scarcer on the global stage, will make it even harder for other countries to afford our products.

Second, while the tariffs have encouraged some companies to “expand their presence or [set] up shop in the U.S.,” they may also incentivize the opposite by discouraging foreign direct investment in the United States. One of the easiest ways for foreigners to reduce their trade deficits with the U.S. will be to reduce their U.S. investments. This is a concern because the U.S. has been a staple for foreign investment for three reasons: relatively low taxes and regulations, an incredibly productive and dynamic workforce, and internationally recognized trade relationships with virtually every country globally. Because of this, we have historically attracted the best and brightest entrepreneurs the world offers. In fact, of the eleven trillion-dollar companies in the world, nine are headquartered right here in America. By harming our ability to export, the tariffs will reduce our potential customer base, further reducing our attractiveness to investors. The tariffs will encourage our trading partners to supplant U.S. trade, not supplement it, starving the U.S. of investment we can ill afford to lose.

Third, in response to the incentives created by the tariffs, foreign countries would benefit from encouraging Americans to invest, not in the U.S., but in their countries instead. By reversing the capital flow, foreign countries' governments can reduce trade deficits with the U.S., lowering the tariffs their businesses face when exporting to the United States. This would hamper the flow of international investments that have long fueled American economic growth, helping to fund everything from factories to Treasury bonds. To reduce their trade deficits, foreigners might even induce American companies with economic incentives or special enterprise zones. With domestic prices inflated and foreign markets less accessible, American companies would undoubtedly see the advantage of these overseas opportunities, which could hollow out the industrial revival the tariffs aim to ignite.

Even more damaging, justifying these tariffs because America is being “ripped off” by other countries, as evidenced by our growing trade deficit, is shaky at best. A trade deficit is nothing more than an accounting identity, not an economic one. They are evidence, instead, that other countries find the U.S. to be one of the greatest opportunities for investment in the world. But to invest in our country, they need U.S. dollars. To get U.S. dollars, they sell us goods and services. Doing so increases our trade deficit, but those dollars return to us as investments. Even when Americans buy foreign goods, those dollars return and create jobs here as foreigners invest in the growth of our country. This is why economists quickly point out that a “trade deficit” is identical to a “capital account surplus.” The latter is the direct foreign investment that Trump seeks to attract. Ironically, by focusing on increasing our exports and decreasing our imports, Trump’s tariff plans will accomplish the opposite.

A Better Path Forward

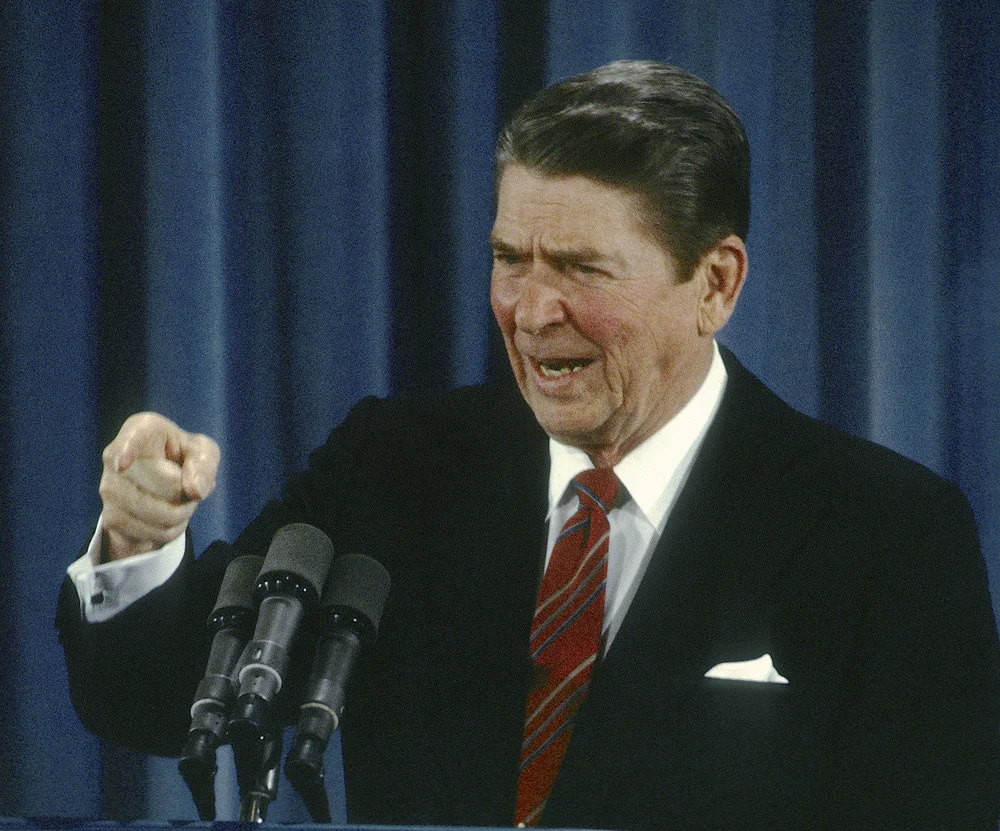

Rather than attracting foreign investment through sticks, we should take a page out of Ronald Reagan’s playbook and use carrots instead. Reagan famously lowered taxes and slashed regulations, particularly on manufacturing and exporting industries. In doing so, he made it easier for the American worker to produce goods and services that could be sold on the world stage. This led to an explosion in American manufacturing and attracted foreign investment, fueling even further growth. The incentives created by Reagan’s policy were clear: investing in America is a good investment. By contrast, despite their intentions, the incentives created by Trump’s misguided tariff gamble will ultimately discourage investment in America.

In addition to his short-term successes, Reagan also laid the groundwork for increased free trade with the rest of the world. Until recently, trading with the United States was remarkably easy, and countries worldwide could count on fairly sensible and predictable trade rules. This was especially true with our allies to the north and south, Canada and Mexico. In doing so, Reagan laid the groundwork for the eventual passage of NAFTA and, later, the USMCA negotiated by Donald Trump during his first term. Both ushered in incredible gains for the US, allowing our economy to grow and flourish into arguably the most successful economy in the world.

The fact is that these tariffs are not just a rotten deal for us today. They’re a rotten deal for us in the future. The longer they remain in play, the more damage they will cause. Rather than a pause, President Trump should take them entirely off the table. Instead, he should pivot to his other policy agendas vis-à-vis economic policy, namely lowering taxes and slashing onerous regulations inhibiting economic activity, including manufacturing. The sooner he makes this shift, the better.

David Hebert is a Senior Research Fellow at the American Institute for Economic Research. Daniel J. Smith is a Professor of Economics in the Jones College of Business at Middle Tennessee State University.

Economic Dynamism

The American Dream Is Not a Coin Flip, and Wages Have Not Stagnated

This paper challenges the prevailing narrative that stagnant wages are causing the American dream to fade. It contrasts subjective public opinion with revised objective intergenerational mobility measures.

Political Economy and the Rise of Commercial Humanism

Western attitudes toward commerce have transformed from early moral condemnation to a modern appreciation that sees trade as socially beneficial.

.webp)

A Bad Business on the Bayou

Chevron finds itself the victim of a political alliance between the tort bar and Louisiana Republicans.

.webp)

Congress Must Shield US Companies from European Regulations

Congress should exercise its constitutional powers over foreign commerce to guard American companies against overregulation by the European Union.

American Aspiration: Our Anti-Dynamism Problem

Dynamism requires agency, creativity, risk tolerance, and sometimes a simple desire for adventure.

Trump's Tariff Fundamentalism

The stock market provides an early glimpse of what the future will hold, as tomorrow’s anticipated outcomes are reflected in the current value of shares.

_(7184104335).webp)

.webp)

.webp)