The Economic Harm That Is Coming

Populist rhetoric might be politically expedient, but policies that expand government control – whether through tariffs, tax hikes, price controls, or labor mandates – don’t empower the people; they hurt them.

Populist rhetoric often promises to uplift the working class, protect the economy from corporate greed, and ensure fairness in the marketplace. But many of the policies that claim to be populist work against the very people they are supposed to help. Politicians on both the left and the right frequently championed deficit spending, protectionism, corporate tax hikes, interest-rate caps, and public-sector union support. Yet, these policies don’t empower workers; they burden workers and ordinary families with slower growth, higher costs, and fewer opportunities.

In today’s populist world, no one wants to touch Social Security and Medicare. Let's take seriously the words of these politicians. Notable examples are President Trump and his predecessor in the White House – when the Social Security and Medicare trust funds expire, we will retain all the benefits and pay for these with borrowed money. That would require hiking the payroll tax, which is a regressive tax and will hurt lower income workers the most. If politicians are tempted to borrow the entirety of the unfunded benefits, it will require borrowing another $124 trillion over 30 years – this on top of the debt we have already accumulated and are in the process of accumulating, which is projected, under rosy scenario, to amount in 2035 to $52 trillion.

I can’t think of a policy that is more opposite to what these populists are claiming they want to achieve. Data show that seniors are overrepresented in the top income quintile. That’s right: As a group, seniors in the United States are doing remarkably well economically. That means that preserving a system that, in essence, transfers large amounts of wealth from the relatively young and poor working Americans to the relatively old and rich is neither populist nor fair.

And excessive debt accumulation is not populist. Leaving aside the crucial question of who will lend us all that money, it is moving us closer to an economic crisis that disproportionately harms working and lower income Americans. We also know that government debt slows economic growth. Slower growth means fewer opportunities to go up the income ladder for those who most need it. More borrowing today will likely mean higher interest rates and payments tomorrow, which will eventually crowd out substantial private investment and government spending on items that people like. Those interest payments do not fund schools, healthcare, or infrastructure; they transfer wealth from taxpayers (most of whom did not vote for the spending) to bondholders. That money could have been used for tax relief, wage increases, or private-sector investment. Of course, more debt today means higher taxes tomorrow.

Even worse, as government debt becomes more unsustainable, it will likely fuel inflation. When inflation erodes wages, it becomes harder for workers to afford basic necessities. Higher interest rates make mortgages, car loans, and credit-card usage more expensive. Meanwhile, government bailouts inevitably favor the politically connected over the average citizen.

Politicians like to champion reckless spending as a populist tool, but do not be fooled: refusing to reform Social Security and Medicare is reckless. These legislators are simply shifting today’s burdens onto future generations. This is not a defense of the working class; it is an abdication of fiscal responsibility and an assault on future workers and families.

Many self-described populists also argue that tariffs and trade restrictions protect American workers from unfair foreign competition. But these policies are taxes on consumers, driving up costs and reducing economic opportunities and real wages. Contrary to the populist claims, U.S. tariffs are mostly a burden for American businesses and families by making inputs, groceries, household appliances, and other consumer goods, more expensive. When the government imposes tariffs on imported products, those extra costs are passed on to consumers through higher prices. After all, protective tariffs are meant to raise the prices buyers pay. A tariff on steel might benefit a handful of politically connected steel producers, but it raises prices for steel-consuming industries, which translates into higher construction costs for everything from cars to homes to infrastructure and more. That hurts workers in the firms downstream of the tariffs.

The inevitable retaliatory tariffs compound this damage. When the U.S. slaps tariffs on imports, other countries respond by imposing their own trade barriers, cutting off access to foreign markets for American farmers, manufacturers, and exporters. For example, recent trade wars have devastated U.S. agricultural exports, forcing the government to bail out farmers to compensate for lost revenue – and increasing the fiscal burden on all Americans.

Protectionist policies invariably create a “seen vs. unseen” problem. The benefit of shielding an industry from foreign competition is visible—factories stay open, and certain jobs are preserved—but the unseen costs, such as fewer jobs in export-driven sectors and higher consumer prices, are much greater. But these remain unseen. In the long run, protectionism doesn’t protect workers generally, it protects politically favored industries at the larger expense of everyone else.

Capping credit-card interest rates sounds like a populist move to protect consumers from financial exploitation—at least that’s what Senators Josh Hawley (R-MO) and Bernie Sanders (D-VT) assert. But in practice, these rate caps are price controls, reducing access to credit for the very people these populist politicians say they wish to help.

Credit-card companies set interest rates to compensate for the high risk of lending to specific borrowers, particularly those with lower credit scores. If the government imposes a strict cap on interest rates, lenders won’t be able to serve these higher-risk borrowers profitably. The result? Many people—especially low-income individuals—will lose access to credit entirely.

Without credit cards, financially vulnerable consumers might resort to other forms of high-cost lending. Even basic financial transactions, such as renting a car or booking travel, become more difficult without a credit card. Instead of capping rates, policymakers should lower borrowing costs by encouraging financial competition and innovation.

Public-sector unions are often portrayed as defenders of the working class, but they operate differently from private-sector unions. Unlike in the private sector—where unions negotiate with and try to get concessions from corporate owners—public employee unions bargain with government officials and try to negotiate concessions paid for by taxpayers. However, these taxpayers have no say as to whether these demands are reasonable or not.

This arrangement creates a perverse incentive that prompts government unions to push for higher wages, expanded benefits, and pension guarantees without regard for economic sustainability. States and municipalities with strong public-sector unions tend to have bloated budgets, excessive debt, and underfunded pension liabilities, which impose higher tax burdens on current and future working families.

Moreover, public-sector unions frequently protect inefficiency and stifle reform. Teachers’ unions, for instance, resist merit-based pay and school-choice initiatives, prioritizing job security for their members over student outcomes. Similarly, government-worker unions lobby against pension reforms even in states where retirement liabilities push budgets toward crisis levels.

Finally, while union workers evoke the idea of blue-collar workers, a large share of public-sector union workers hold a bachelor's degree or higher. This is especially true in education.

A genuinely populist approach would focus on protecting taxpayers and ensuring that the government serves the public efficiently, not acting as a wealth-redistribution mechanism for politically connected unions.

Raising the corporate income tax is another favorite policy of right—and left-wing populists who claim to be fighting corporate greed. However, multiple economic studies show that workers bear much of the burden of corporate taxes. When corporate taxes increase, businesses cut costs by reducing jobs, lowering wages, and scaling back investments. A higher corporate tax rate makes American businesses less competitive globally, discouraging firms from expanding or hiring. It also reduces incentives for capital investment, a key driver of productivity and wage growth.

Moreover, corporate tax increases do little to make the tax system fairer. Corporations pass these costs to consumers through higher prices, meaning ordinary people ultimately pay more for goods and services. If we want stronger wages and job growth, we should make it easier—not harder—for businesses to invest, innovate, expand, and hire.

In the end, many of these alleged ‘populist’ policies are just theater. Real populists fight cronyism, limit government overreach, and ensure economic freedom. That means ending all subsidies and government-granted privileges for corporations. These privileges raise consumer prices and are unfair to everyone who is not a well-connected player in Washington, D.C. It also means no more bailouts to banks, airlines, aircraft producers such as Boeing, and other so-called “national champions.”

It means reducing the size of government, lowering taxes, reducing regulation, and slashing government debt, which will produce greater economic opportunity for all. Fiscal responsibility is important to ensure economic stability and to protect future generations from financial ruin. It means embracing free markets. Competition and innovation—not government intervention—drive prosperity and create real opportunities for workers.

Populist rhetoric might be politically expedient, but policies that expand government control – whether through tariffs, tax hikes, price controls, or labor mandates – don’t empower the people; they hurt them. If we truly want an economy that works for all, we must reject these false populist policies and champion policies that promote growth, competition, and individual freedom.

Veronique de Rugy is the George Gibbs Chair in Political Economy and Senior Research Fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. She is also a nationally syndicated columnist and contributing editor to Civitas Outlook.

Economic Dynamism

The Causal Effect of News on Inflation Expectations

This paper studies the response of household inflation expectations to television news coverage of inflation.

.avif)

The Rise of Inflation Targeting

This paper discusses the interactions between politics and economic ideas leading to the adoption of inflation targeting in the United States.

Why Can't the Middle Class Invest Like Mitt Romney?

Why can’t middle-income Americans pay effectively no taxes on investments like the wealthy do?

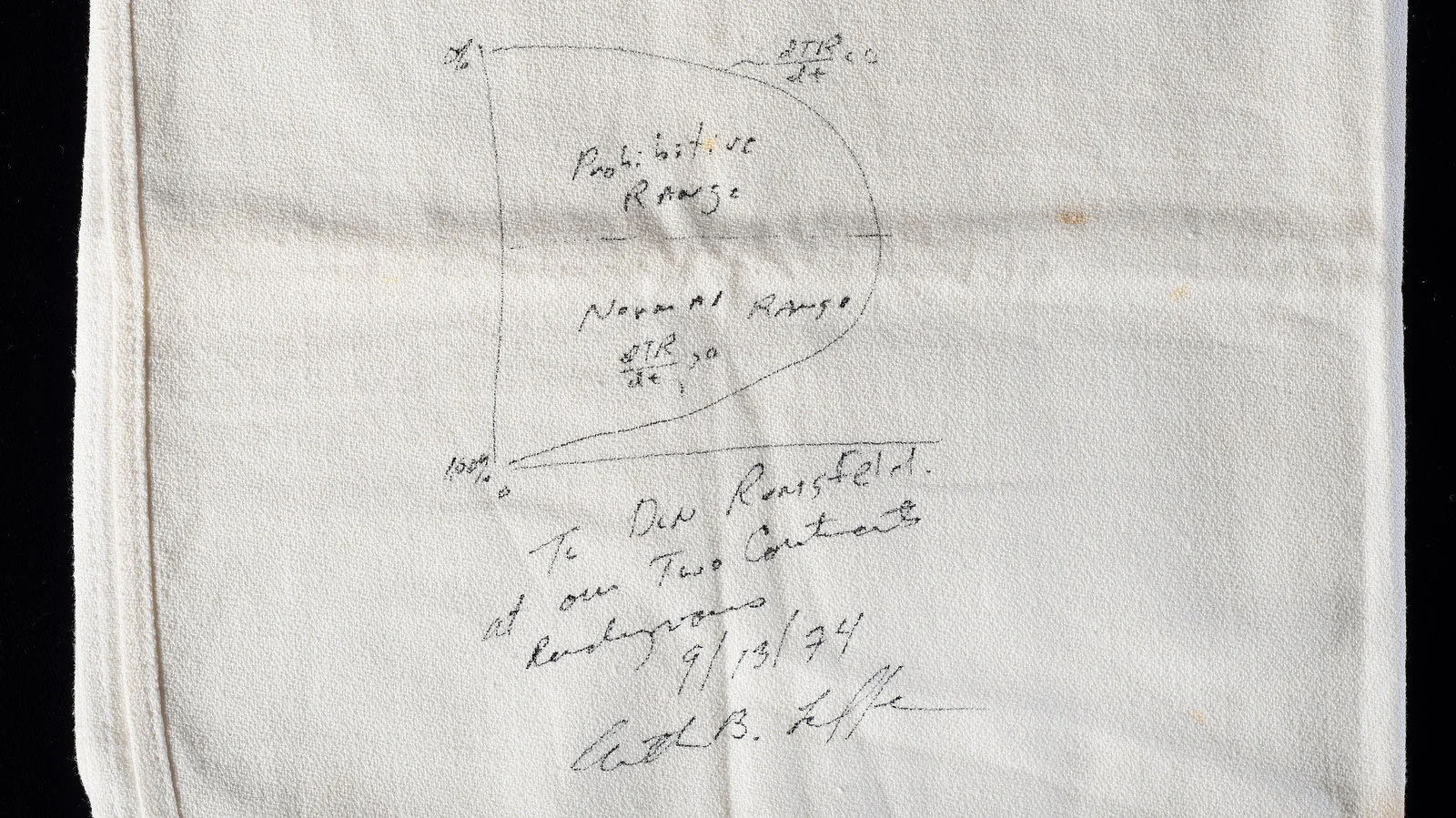

The Revenge of the Supply-Siders

Trump would do well to heed his supply-side advisers again and avoid the populist Keynesian shortcuts of stimulus checks or easy money.

.jpg)

.jpg)