YooKay plc

One could be forgiven for thinking that Keir Starmer is a dud, and the Tories will come roaring back in 2029.

On July 4th, 2024, Sir Keir Starmer’s Labour Party won a true landslide. Last month, Labour was forced to filch a warmed over Tory policy from before that election: funding increased defense spending by cutting foreign aid. Conservative opposition leader Kemi Badenoch thanked him, acidly, for “taking my advice.”

Labour and Starmer are both generally and specifically unpopular.

Since the election, the government has shown itself to be afflicted by a sort of Midas Touch in reverse: everything it lays its hands on turns to shit. Britain’s energy bills—both for households and industrial consumption—are the highest in the developed world. The police routinely arrest people for mean tweets, while knife crime in London balloons. There has been open support in London’s streets for proscribed terrorist organizations since October 8th, 2023. Paedophiles get powder-puff sentences while—despite the UK’s reputation as “TERF Island,”—a Scottish nurse is forced to undress in a mixed changing room. Until Elon Musk pressed the issue, there was widespread “nothing to see here” behavior in response to Pakistani Muslim grooming gangs.

Starmer, meanwhile, discovered that the country’s sclerotic civil service has booby-trapped the British state against any future governments, including Labour ones. It was long believed that this go-slow, work-to-rule behavior was something it only did to Tories. Not so. Starmer is now confronted with levers that engage no gears and move nothing, let alone worlds, no matter how hard or how often he pulls them. This has translated into an inability to build anything, not even wind farms—which Starmer’s loopy Energy Secretary, Ed “Net Zero” Miliband, actually wants.

As happened to the Tories, Starmer’s attempts to remove illegal immigrants and foreign criminals are being stymied in courts beholden to gimcrack human rights instruments. In one grimly amusing case, an Albanian criminal—already stripped of his UK citizenship in 2021—had his deportation halted because his son “didn’t like foreign chicken nuggets.”

How did we get here?

The devil is in the detail as ever in first-past-the-post (FPTP) parliamentary systems. For US readers, it’s easiest to draw comparisons if I tell you that any UK political party winning the same vote share as Donald Trump did in November (49.9 percent) would consider itself to have won the electoral Olympics, to have landed on the political equivalent of “Free Parking” in Monopoly. The last time a British political party came anywhere near that was in 1951, with Labour’s all-conquering Clement Attlee winning 48.8 percent.

By contrast, Labour’s 2024 landslide—nearly two-thirds of Commons seats for a total of 411—discloses little affection, based as it is on less than sixty percent turnout and just over a third of the UK’s votes. This is only slightly more than Labour won in 2019—when Jeremy Corbyn, now an independent MP, was leader—and considerably less than Corbyn’s 2017 achievement (40 percent), also in a losing cause. Labour’s eventual 2024 vote share—33.8 percent—was lower than any opinion poll.

Labour’s support was thus a mile wide and an inch deep: it won a House of Commons landslide, but not an electoral one. Many of Starmer’s MPs—including Cabinet ministers like the (competent) Health Secretary Wes Streeting—sit on wafer-thin margins, making them even more vulnerable than usual in the event of by-elections and internal party conflicts. Talk of US-style “supermajorities” in the UK is silly—you don’t have a different kind of power with a big majority in parliamentary systems. If anything, FPTP has given Labour’s fractious, divided electoral coalition a spurious patina of unity. A divided electoral coalition, of course, helped do for the Tories when they had a large majority.

Fast-forward nine months, and it’s fair to say Labour’s loveless landslide has come back to bite it in the bum, precisely because there’s no affection underlying that huge majority. People proclaiming Starmer as the heir to Tony Blair (who was enormously popular, especially in 1997) have been bitterly disappointed. Labour hasn’t quite hit July 2024 Tory levels of unpopularity yet, but there’s still four-and-a-half years to go.

This also explains why—with Reform surging in the polls, routinely coming in first place (while Labour and Conservatives duke it out for second)—there’s no chance Starmer will go to the King and call an early election. Reform’s leader, Nigel Farage, would have to die for that to happen. The problem with this strategy—forced on Starmer because of Labour’s radical unpopularity—is that Reform is inching towards the 30 per cent vote share you need to be a serious political party in these Islands. At time of writing, all four major parties, note (Labour, Conservative, Reform, Liberal Democrat) are currently polling below 30 percent.

The longer Starmer avoids calling an election, the worse Labour’s predicament will be, and yet the less likely any election will be called. Falling below 30 percent ruined the Liberals in 1924 and 1929. It also destroyed the Liberal-SDP Alliance in 1983, where the combined parties got 25 percent of the vote but only 12 seats. And, last year, it gave the Conservatives what can genuinely be described as a “near death experience,” with the party only saved (23.7 per cent vote share for 121 MPs) because some of its core support is geographically concentrated. The 2024 election was the worst result in the party’s history, and given the Tories are the world's oldest and most successful political party, Kemi Badenoch, the party’s new leader, has been handed the most poisoned of chalices.

Why is Farage so popular?

One could be forgiven for thinking that all this means is that Starmer is a dud, and the Tories will come roaring back in 2029. British politics can be a bit of a Punch & Judy show, and this sort of outcome would evince that characteristic.

Not so fast.

The problem for Badenoch is that Labour’s travails (sometimes over the same issues Conservatives struggled with, like immigration) were preceded by fourteen years of inept Tory governance. Apart from talking right and governing left in the last five years of its time in office, David Cameron accepted Blair’s hiving off much of parliament’s power to unelected Quangos. Quangos, translated into American, are akin to “non-departmental public bodies” or “government-sponsored enterprises.” The quangocracy is at the heart of Britain’s “Blob” and is a significant reason neither Labour nor Conservative governments can do anything. Meanwhile, the civil service busies itself with ever more baroquely colourful lanyards (all the better to wear while evincing what used to be called “workshy behaviour”).

Farage, of course, is helped here precisely because he’s never been in government. Being an MEP is not being in government: that was always a significant part of the issue for anyone elected to the European Parliament. This seems strange to say—given how familiar he is to Americans because of his personal friendship with Trump and role in bringing about Brexit—but he only became a sitting MP (for Clacton, in Essex) last year. In that sense, he shares a background with Trump, who, prior to 2016, had also never been in government (or opposition, for that matter).

This is likely how Farage and Reform maintain their popularity despite catching a dose of internecine political spats disease off the Tories. Ostensibly about differences over immigration policy—Reform is a notorious policy vacuum—it’s really a clash between two giant egos. Farage’s opponent in this is Rupert Lowe, Reform’s MP for Great Yarmouth and the multimillionaire former chairman of Southampton Football Club.

Labour, perhaps inevitably, provides endless political fodder. This ranges from paying Mauritius to take the strategically important Chagos Islands—over the heads of the Chagossians, note—off Britain’s hands or replacing Admiral Nelson’s portrait in Parliament with a simultaneously insipid and hubristic attempt to make a sitting Cabinet Minister look like a cross between the late Queen and a Roman Empress. This in a country where it was once considered vulgar to have portraits of any living person other than the King hanging in official buildings or on postage stamps. The rationale for the custom was that it prevented Britain from looking like a tin-pot dictatorship, something that clearly worries Labour not a bit.

Yes, the Tories are also able to make hay with this sort of nonsense—and people do laugh at Badenoch’s jokes about it; she has natural comic timing—but this does not benefit her party at all because everyone can remember what they did in (very) recent times. If a week is a long time in politics, 14 years is an eternity.

Britain, meanwhile, staggers blindly on, leaderless and rudderless. The drift is best captured by an TwitterX account, YooKay Aesthetics. Its anonymous owner sources (or perhaps takes; this is unclear) photographs of things ranging from shops going card only because staff can’t count change accurately or illegal asylum-seekers capturing swans and eating them to Keir Starmer attempting to gain a tiny bit of reflected glory by endorsing the British Kebab Awards. It is a black and bitter satire on those who see no problem with a once great nation being reduced to YooKay plc, a hotel but never a home.

Helen Dale is a Senior Writer at Law & Liberty. She won the Miles Franklin Award for her first novel, The Hand that Signed the Paper, and read law at Oxford and Edinburgh. Her most recent novel, Kingdom of the Wicked, was shortlisted for the Prometheus Prize for science fiction. She writes for various outlets, including The Spectator, The Australian, Standpoint, and Quillette. She lives in London, is on Substack at www.notonyourteam.co.uk, and on TwitterX @_HelenDale.

Politics

.webp)

Liberal Democracy Reexamined: Leo Strauss on Alexis de Tocqueville

This article explores Leo Strauss’s thoughts on Alexis de Tocqueville in his 1954 “Natural Right” course transcript.

%20(1).avif)

Long Distance Migration as a Two-Step Sorting Process: The Resettlement of Californians in Texas

Here we press the question of whether the well-documented stream of migrants relocating from California to Texas has been sufficient to alter the political complexion of the destination state.

%20(3).avif)

Who's That Knocking? A Study of the Strategic Choices Facing Large-Scale Grassroots Canvassing Efforts

Although there is a consensus that personalized forms of campaign outreach are more likely to be effective at either mobilizing or even persuading voters, there remains uncertainty about how campaigns should implement get-out-the-vote (GOTV) programs, especially at a truly expansive scale.

California job cuts will hurt Gavin Newsom’s White House run

California Governor Gavin Newsom loves to describe his state as “an economic powerhouse”. Yet he’s far more reluctant to acknowledge its dramatically worsening employment picture.

An anti-woke counter-revolution is sweeping through the media

From Hollywood to the newsroom, the hegemony of the ‘progressives’ is finally faltering.

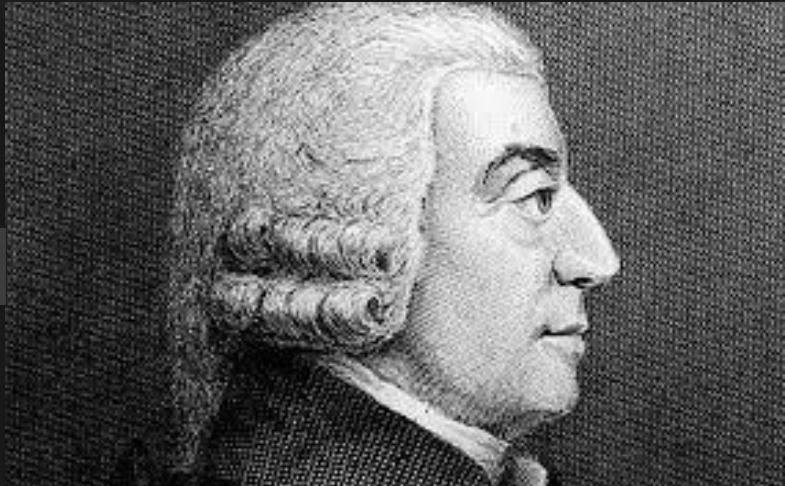

What Adam Smith’s Justice Teaches Us About Stealing Benefits

There is a constant tension in liberal systems between the shared trust necessary for the system's survival and the use of public entitlements paid for at public expense.

Indiana, D.C., and Purchased Submission

The clear lesson for all Americans is this: Allowing federal transfers into your state also means giving DC a say in state and local issues.

%20(1).jpg)