Return to the Monroe Doctrine

Trump returns to the grand strategic principles that have guided US foreign policy for the past two centuries.

Even before assuming office, Donald Trump has set American diplomatic relations afire with seemingly outlandish claims to new territory. He has floated a purchase of Greenland, the return of the Panama Canal, and a mention of Canada as the 51st state. Critics are not sure whether to take Trump literally, seriously, or neither. They are apt to accuse Trump (inconsistently) of being either an isolationist or an imperialist. The truth is that he is neither. Rather, Trump seems instinctively to be calling for a return to the grand strategic principles that have guided US foreign policy for most of the past two centuries. In particular, he seems to be calling for the renewal of the classic Monroe Doctrine in some form – that fundamental American policy, announced by President James Monroe in 1823, that structured our relations with our hemispheric neighbors throughout most of the 19th century and beyond. Whether or not Trump himself consciously wishes to revitalize these principles, the effect of his policies may be to do exactly that.

And that may be all for the good, both internationally and domestically. Internationally, Trump may want to place the defense of this region on firmer ground, safeguarding both this country and its hemispheric neighbors against Chinese penetration to the south and Russian encroachment from the north. Domestically, securing the Western Hemisphere could provide the basis for a new consensus that brings together a nation scarred by our setbacks in Afghanistan and Iraq, skittish about further American military ventures far abroad, and yet worried about the rise of China and the ambitions of Russia.

Greenland

However outlandish some of Trump’s ideas might seem at first glance, they, in fact, merit closer inspection. Greenland sits in a strategically sensitive location near the Arctic that governs the North Atlantic shipping routes between the United States and Western Europe. Even before American entry into World War II, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the U.S. Navy to establish an effective protectorate over the island to protect convoys to England. During the Cold War, the United States and NATO established bases in Greenland that launched nuclear-armed bombers and hosted patrols for Soviet submarines. If global warming makes more of the Arctic accessible, Greenland will provide an equally valuable base for commercial and military competition with Russia and China. Greenland itself also possesses valuable mineral deposits, including the rare earths that are necessary for high-tech and advanced military products.

Greenland is currently part of the tiny kingdom of Denmark (though Denmark considers Greenland self-governing and has recognized Greenland’s right to self-determination). While a NATO ally and EU member, Denmark is no major power. It has a population of only 6 million; only 56,000 call Greenland home. It could not seriously oppose an American effort to re-occupy the massive island. Not that the US should contemplate wresting Greenland from Denmark or its own inhabitants without their consent. Greenland and Denmark should welcome a greater American presence – it would send a signal of American commitment to NATO and would open the island for greater economic development and growth. Trump can and should create the conditions for the inhabitants of Greenland to seek a closer relationship with the United States.

In any case, Trump does not need to take full sovereignty over Greenland to achieve American security goals. The United States could leave Greenland’s formal title in the hands of tiny Denmark while seeking the right to full military control over the territory. Other models are available, including the “free association” that currently governs our relations with Palau and Micronesia. Yes, Trump's Bold Greenland Plan Could Actually Work. Property rights have been likened to a bundle of sticks that the owner can sell off one at a time – the principle governs in international politics, too. The United States could exercise military control over Greenland and assist in its economic development while reserving other aspects of sovereignty in the hands of Greenland’s inhabitants.

The Bigger Picture: Looking North and South

Acquiring Greenland should only proceed because it forms part of a coherent and broader foreign policy. Trump’s recent remarks strongly suggest that he instinctively seeks a revival (in some form) of the Monroe Doctrine. Trump’s chief of staff in the White House National Security Council during the first term, Alexander Gray, likened Trump’s vision of foreign policy to that of the nineteenth-century statesman John Quincy Adams, who, as President James Monroe’s Secretary of State was in great measure the author of the Monroe Declaration. Trump is “really talking about … the Western Hemisphere First, and America’s interest in the Western Hemisphere,” Gray said.

Likewise, Trump’s selection of gifted Latin American experts for high positions in his Administration – starting with Senator Marco Rubio, his nominee to be Secretary of State, and Christopher Landau as his deputy – indicates that the Western hemisphere will be the primary focus of his foreign policy in his next term. This strategic shift of attention – looking North and South first – may prove to be a wise and necessary reordering of American priorities.

Unlike much of Trump’s domestic agenda, his foreign policy does not seek to trigger a radical revolution. Instead, he instinctively seeks a return to fundamental American principles. As they have evolved over the course of America’s history, American national security has come to have five priorities.

The Five Chief Priorities of American National Security

Its first and most important policy is to protect the continental United States. Although we have not had to worry about homeland defense since the War of 1812 seriously, it is still the basic starting point for protecting the American people. (The events of 9/11 disturbed our sense of being insulated from outside attacks and raised fears of future terrorist attacks here, but did not raise a threat of foreign invasion.) Historically, American leaders have conducted not defense, but offense. They have steadily expanded the homeland from thirteen colonies hugging the Eastern seaboard to the continent-wide behemoth straddling the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

Second, the United States has sought to exercise a policy of strategic denial over the Western Hemisphere. If there were ever an attack on the United States, it would most likely come from launching pads in our own region, as they did from Canada in the War of 1812. We cannot tolerate hostile governments in a region that is so rich in population and physical resources and yet also has the ability, because of its proximity, to exacerbate instability in the United States. Mass migration, drug smuggling, sex trafficking, and criminal gangs in Mexico and South America have a direct impact on health and safety within our borders. Despite these challenges, the United States has, for the most part, successfully exercised a benevolent hegemony – one without direct rule – over the Western Hemisphere and prevented the rise of any permanent competitors there.

We have indeed acquired territorial possessions by war and conquest, as well as by purchase or treaty, from other nations. These include the Kingdom of Hawaii, Mexico (California and southern Arizona); Russia (Alaska), Spain (Florida and Puerto Rico), France (the Louisiana Purchase), Denmark (the Virgin Islands), and Britain (Oregon). It is also true that our hegemony has not always been seen as “benevolent”: many Chileans and Guatemalans remain bitter over our interventions in their countries (although many Venezuelans wish we would intervene in theirs). But we have also extended a protective shield over our neighbors that has guarded most of them, as well as ourselves, from nineteenth-century European imperialism and twentieth-century Nazism and Communism.

It is the remaining three foreign policy goals that have spurred concerns of overreach when our ends have exceeded the available means. America’s third strategic goal seeks to prevent either Europe or Asia from falling into the hands of an adversarial power. Both continents have levels of population, wealth, and industry that could pose a serious security threat if unified against us. And, as the English geopolitical thinker Halford Mackinder argued a century ago, whoever controls the global heartland – the great mass of Eurasia – controls the planet. The United States has sought, by all means, to avoid that outcome.

Thus, President Woodrow Wilson led the nation into War in 1917 to prevent Germany and Austria-Hungary from prevailing and so dominating the European continent. FDR similarly led us into World War II to prevent Nazi Germany from controlling Europe and Japan from doing the same in Asia. In the Cold War, we established NATO to prevent the Soviet Union from dominating Western (as well as Eastern) Europe, and we waged war in Korea and Vietnam to stop Communism’s spread in Asia. Reconstructing our allies and even former enemies (Germany and Japan) to resist Soviet and Chinese communism caused these States to support capitalism and democracy in both Europe and Asia – with astounding improvements in economic wealth and individual freedom. In none of these wars did the United States, unlike our Asian and European competitors, seek territorial expansion or colonies – in fact, we reconstructed our former enemies into allies and sought to spread markets and democracy. By pursuing our interests, the United States undoubtedly served the interests of greater humanity. Nevertheless, defending the West came at significant cost in blood, in Korea and Vietnam, and treasure.

America’s fourth and fifth strategic goals emerged as our wealth and global position rose in the 20th Century. We have sought to control the global commons, such as the sea, air, and space, and the new one of the internet. While the United States has an interest in preventing any hostile nation from controlling the mediums for attacking the homeland, it has patrolled these areas to allow free trade and open navigation for the benefit of all. Lastly, the United States has allowed its protection of Europe and Asia and of the world’s commercial networks to slip into a greater mission to secure global stability and protect the human rights of all, without regard to the discrete benefits for the United States. It is in seeking to bring democracy and capitalism to foreign lands not directly in our national security interests that American national security policy has run aground. Donald Trump’s victory represents a retrenchment from the high costs and smaller benefits of this virtually unlimited strategy to better the world.

The Importance of the Americas to the United States

Once upon a time, American leaders would have needed no reminder of the overriding strategic significance of the Western Hemisphere. For the past two centuries, the US has paid close attention to our American neighbors. We are closely tied to them in fundamental ways: economically, ideologically (especially since the wave of democratization that swept through Latin America after the end of the Cold War), culturally and (in the case of Anglophone Canada) linguistically. Our histories are intertwined: both the United States and modern Canada grew, in different ways, out of the American Revolution, and Canadians and Americans fought together as allies in several wars. As for the Latin nations, the nineteenth century American statesman Henry Clay remarked (as those then-new nations were struggling to throw off Spanish colonialism) that they were “our neighbors, our brethren occupying a portion of the same continent, imitating our example and participating of the same sympathies with ourselves.” Today, millions of US voters whose family origins lie in Latin America profoundly influence our domestic politics.

Indeed, our ability to project power into areas outside the hemisphere while remaining secure at home rests on amicable relations with the rest of the Americas. As two leading regional experts wrote in 2021:

From a geostrategic perspective, Latin America and the Caribbean – particularly the countries of the Caribbean basin – represent the most direct vector for political instability or security threats to reach the United States … Only a country not constrained by a balance of power near its borders can decisively affect the balance of power overseas. We should remember that in 1963, President John F. Kennedy risked a global nuclear war over the Soviet effort to station nuclear missiles on the soil of a nearby Caribbean nation.

Our strategic inattention to the Western hemisphere is a fairly new development. For most of this century, despite the good intentions of some of our leaders, Latin America and the Caribbean have languished from our strategic neglect. They have received little attention and elicited few major initiatives from this country. But as recently as the Reagan Administration, Jeanne Kirkpatrick declared that Central America was “the most important region in the world.” President Ronald Reagan himself, in his 1987 State of the Union Address, declared that “[o]ur commitment to a Western hemisphere safe from aggression did not occur by spontaneous generation on the day that we took office. It began with the Monroe Doctrine in 1823 and continues our historic bipartisan American policy.” Reagan demonstrated his concern over Soviet penetration of our Latin neighbors in a variety of ways, notably by supporting democracy in Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Uruguay, by laying the foundation for NAFTA, and by frequent visits to and from the region both on his part and in the person of his Secretary of State George Shultz. Reagan also did not shy away from armed intervention in the Caribbean island of Grenada and by arming the anti-Communist Nicaraguan “Contras.” Trump’s emerging policies seem to harken back to Reagan’s. If Trump’s policies were to be modeled on Reagan’s, they would include actively pursuing free trade deals with Mexico and Canada and closer co-operation in areas like mutual defense and immigration.

To be sure, there is a crucial ambiguity in Trump’s announcements so far. On the one hand, he may be outlining a policy that contemplates and even routinizes US military intervention in our neighbors’ territory and political affairs. If so, his future policy would seem like President Theodore Roosevelt’s “Corollary” to the Monroe Doctrine. Roosevelt’s Corollary was promulgated in the age of European (and American) imperialism. Roosevelt proclaimed it not long after the decisive American victory in the Spanish-American War, which ousted Spain from its remaining colonial possessions in this hemisphere and confirmed the US’ supremacy within it. Roosevelt further secured US hemispheric ascendancy by building and controlling the Panama Canal.

The “protective imperialism” of Roosevelt’s Corollary elbowed aside other potential Great Powers with regional interests by warning them not to exploit Latin American financial indebtedness and political instability to justify intervening in their affairs. Especially in the hands of Roosevelt’s successors Taft and Wilson, this doctrine underpinned US interventions in the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Nicaragua, and Mexico. Although we think it unlikely, it is at least conceivable that Trump would re-launch that kind of policy. And the statement in his Inaugural Address that the US will take back the Panama Canal might indicate as much. However, his first-term decision not to intervene militarily in Venezuela suggests that that is not his intention.

Returning to the Monroe Doctrine?

On the other hand, Trump may be envisaging a policy closer to the original Monroe Doctrine than the Roosevelt Corollary. The core of the Monroe Doctrine – which has remained the central preoccupation of US interest in the hemisphere for two hundred years – has been a policy of strategic denial, i.e., of preventing powerful rivals from outside this hemisphere from acquiring strategic footholds in Latin America or from impairing our vital security interests within it. Thus, while the Roosevelt Corollary focuses on dominating the internal affairs of our Latin neighbors, the Monroe Doctrine concerns the intrusion of outside powers into the hemisphere.

If protecting US national security was perhaps the paramount objective of the original Monroe Doctrine, the principle of anti-colonialism was the other great pillar on which the Doctrine rested. As Monroe and his Cabinet sought to formulate the ideas that eventually appeared in his address to Congress, some of the European Great Powers, no longer distracted by the Napoleonic Wars, had begun to cast covetous eyes on the Americas. Russia had entered a claim (soon withdrawn) to the northern Pacific. Under a restored Bourbon monarchy, France had crushed a revolution in Spain, reinstated another Bourbon on its throne, and was thought to be considering an alliance with Spain to recover Spain’s rebellious South American colonies or, perhaps, to set up semi-autonomous kingdoms in some of them, ruled over by Bourbon princes. (Portugal had already provided a model for this arrangement by making its vast former colony Brazil a co-equal kingdom.)

These developments concerned Americans, not only because they might threaten our security but also because they were offensive to the anti-monarchical and anti-colonial principles on which our own Republic was based. Recording a debate in Monroe’s Cabinet, Adams wrote:

Considering the South Americans as independent nations, they themselves, and no other nation, had the right to dispose of their condition. We have no right to dispose of them, either alone or in conjunction with other nations. Neither have any other nations the right of disposing of them without their consent.

Respect for the nascent republican institutions created in the new Latin American nations and fear that those new nations might revert to monarchism was deeply embedded in our constitutional grain. As the historian Jay Sexton points out, two of our founding documents – the Constitution of 1787 and the Northwest Ordinance of the same year – established a decentralized, federal political system that stood in stark contrast to the vertical model of the Old World empires, which ruled over their far-flung dependencies from a governing apex in London, Paris or Madrid.

In fact, the two central objectives of Monroe’s policy – protecting US national security and opposing European colonial expansion in the Americas – were interdependent. In his diary, Adams described the Monroe Administration’s deepest fears:

Russia might take California, Peru, Chili [sic]; France, Mexico – where we know she has been intriguing to get a monarch under a prince of the House of Bourbon, as at Buenos Ayres [sic]. And Great Britain, as her last resort, if she could not resist this course of things, would take at least the island of Cuba for her share of the scramble. Then what would be our situation – England holding Cuba, France Mexico?

Pursuing Strategic Denial

History shows that a policy that emphasizes US military intervention to the exclusion of all other methods (trade, development, investment, close diplomatic relations) is not the only or the best means of achieving the aim of strategic denial. Thus, faced with the danger of Nazi penetration of the region, President Franklin Roosevelt courted the amity of Latin America in his “Good Neighbor Policy.” FDR de-emphasized the military aspects of strategic denial and stressed economic and diplomatic ties. Far from renouncing the Monroe Doctrine, however, FDR transformed it from a unilateral pronouncement to a multilateral pact, winning Latin American support for the position adopted at the Havana Conference in 1940 that the US and any other American state could take action in a “manner required for its defense or the defense of the continent” against any power outside the hemisphere that violated the territorial or political integrity of a Western Hemisphere state.

It is far too soon to tell, but Trump may, in fact, want to pursue a policy like Ronald Reagan’s, which wove together themes of trade, diplomacy, and consultation with the occasional and limited use of force. Trump may believe that our current global commitments are unsustainable. Those commitments involve us in the defense of vast swathes of the globe, running from Ukraine and the Baltic States to Taiwan and the South China Sea. Trump may think that the US simply can no longer carry that burden, at least not without substantially more help from wealthy Western European allies, Japan and Taiwan. He may also have concluded that we have neglected the affairs of our hemisphere to the point that China’s expanding footprint on the region, together with Russia’s and Iran’s, now pose a critical threat both to our national security and to the democratic institutions of (most of) our near neighbors. In short, he may think that a foreign policy scaled to our hemisphere is better suited to our needs and capabilities than one scaled to the entire globe.

In his classic 1975 study, The Making of the Monroe Doctrine, the historian Ernest May observed that from the very beginning, our Founders conceived of the United States as, potentially, an empire rather than a mere nation. But they were uncertain what kind of “empire” it was to be. The fundamental question was whether it should be a “geographical” empire or an “ideological” one. Monroe was more inclined to the latter view, and John Quincy Adams was more inclined to the former. Were we to be “a Rome merely of Caesar or a Rome also of St. Paul”? Under Trump, the question is again presenting itself. His emerging answer seems to be Caesar, not St. Paul.

John Yoo is a distinguished visiting professor at the School of Civic Leadership and a senior research fellow at the Civitas Institute at the University of Texas at Austin, the Heller Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley, and a nonresident senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute.

Robert Delahunty is a Washington Fellow of the Claremont Institute Center for the American Way of Life.

Politics

.webp)

Liberal Democracy Reexamined: Leo Strauss on Alexis de Tocqueville

This article explores Leo Strauss’s thoughts on Alexis de Tocqueville in his 1954 “Natural Right” course transcript.

%20(1).avif)

Long Distance Migration as a Two-Step Sorting Process: The Resettlement of Californians in Texas

Here we press the question of whether the well-documented stream of migrants relocating from California to Texas has been sufficient to alter the political complexion of the destination state.

%20(3).avif)

Who's That Knocking? A Study of the Strategic Choices Facing Large-Scale Grassroots Canvassing Efforts

Although there is a consensus that personalized forms of campaign outreach are more likely to be effective at either mobilizing or even persuading voters, there remains uncertainty about how campaigns should implement get-out-the-vote (GOTV) programs, especially at a truly expansive scale.

California job cuts will hurt Gavin Newsom’s White House run

California Governor Gavin Newsom loves to describe his state as “an economic powerhouse”. Yet he’s far more reluctant to acknowledge its dramatically worsening employment picture.

An anti-woke counter-revolution is sweeping through the media

From Hollywood to the newsroom, the hegemony of the ‘progressives’ is finally faltering.

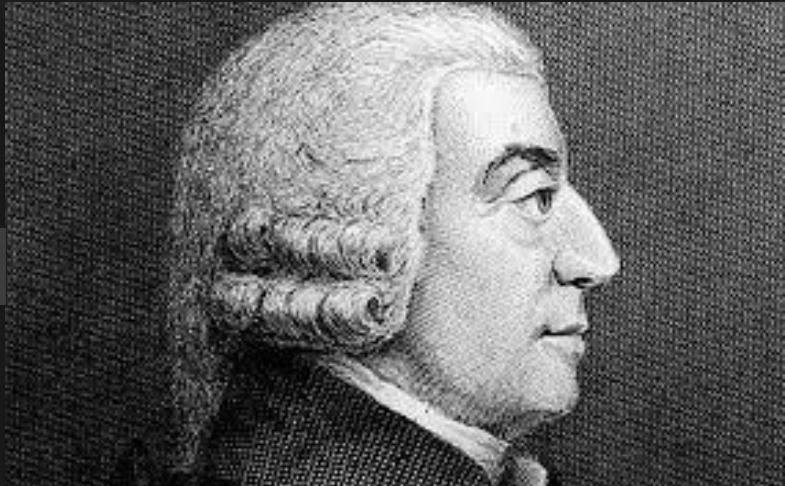

What Adam Smith’s Justice Teaches Us About Stealing Benefits

There is a constant tension in liberal systems between the shared trust necessary for the system's survival and the use of public entitlements paid for at public expense.

Indiana, D.C., and Purchased Submission

The clear lesson for all Americans is this: Allowing federal transfers into your state also means giving DC a say in state and local issues.

%20(1).jpg)