Foucault’s “Discipline and Punish" at 50

Did Foucault's Discipline and Punish succeed in unmasking bourgeois society or reveal the limits of his contact with human reality?

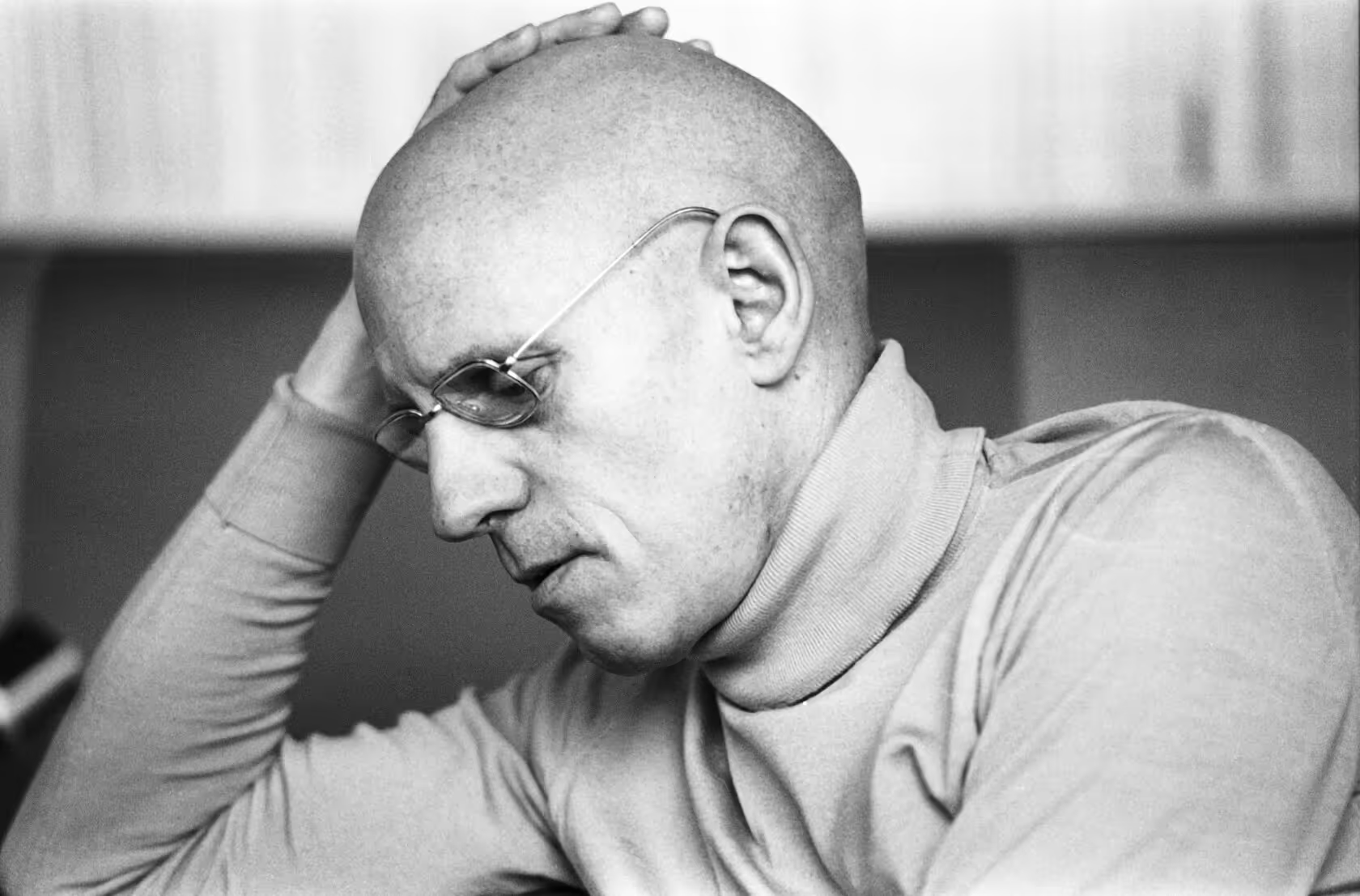

Michel Foucault (1926–1984) is both dead and lives on powerfully, if subterraneously, in several contemporary forms of thought. A quick survey of some contemporary works will indicate his contemporary presence. Then, we’ll look directly at his thought with the help of two philosophical scholars: the late Roger Scruton and the Brazilian philosopher and scholar J. G. Merquior.

In his recent book, The Narrow Passage: Plato, Foucault, and the Possibility of Political Philosophy (2023), Glenn Ellmers effectively utilizes Foucault in analyzing a contradiction at the heart of today’s progressive thought. On one hand, they follow Hegel and the American Progressives in extolling the rule of expertise and replacing genuine democratic self-rule with the Administrative State staffed by such experts. But on the other hand, they roundly deny reason’s ability to discover objective truth: any such claims are pretexts for power. After Nietzsche, Foucault is the source of this thought. As Ellmers points out, one can observe that the pretense of objective knowledge can serve those wielding power, such as Anthony Fauci (“attacks on me … are attacks on science”), during the COVID gaslighting and censorship.

Other scholars have traced the connection the other way, pointing out that proponents of postmodern thinking have sometimes qualified their characteristic claim that all “truth” is a social construct by acknowledging relatively stable identities that can be empowered. Those pointing out this convenient incoherence include Mike Gonzales and James A. Lindsay, who include Foucault in their analyses of identity politics and Critical Race Theory. In his book, The Plot to Change America: How Identity Politics is Dividing the Land of the Free (2020), Gonzales highlights the fabricated nature of various racial classifications created for political purposes, outlining their history, and explores the use of Foucault in this empowerment agenda. After some hesitations, Lindsay has come around to seeing contemporary Critical Race Theory as the bastard child of Marx via Marcuse and of Foucault via Kimberlé Crenshaw and others. Hegel’s Master-Slave dialectic, updated or transferred by Marx to economic classes, was “culturalized” by Marcuse, as he turned to new “proletariats” on which to pin Revolutionary hopes. At the same time, Crenshaw adopted and stabilized “discourse-created” identities to undergird the key concept of “intersectionality.” Postmodern “deconstruction” was necessary for overturning racist, misogynist, patriarchal, Christian, and “liberal” orders, but could be taken too far, leaving “victims” with no reality to defend or assert. Strategic compromises or adulterations were required. As is always the case with ideology, theory serves practice.

Philosophical Critics

Before these recent more popular exposés, two philosophically minded scholars took on Foucault directly. The late Roger Scruton devoted a chapter to Foucault in his flamboyantly entitled but still deeply serious and penetrating work, Fools, Frauds, and Firebrands: Thinkers of the New Left (2015; reprinted 2019). And before him, the Brazilian academic writer, literary critic, philosopher (and diplomat) J. G. Merquoir devoted an entire study to Foucault’s thought, including his posthumously published History of Sexuality. Simply entitled Foucault, it appeared in 1985, a short year after his death.

Merquior placed Foucault in the post-war currents and constellations of French thought, beginning with structuralism and then post-structuralism. What focused and motivated Foucault’s investigations was the ambition to write (in his own paradoxical words) “a history of the present,” that is, a “genealogy” of “modern reason” in its various forms as they constitute modern society. In this general endeavor, he was far from alone. This sort of project was widespread in the twentieth century and could define postmodernism as a whole and other twentieth century thinkers. Jacques Derrida sought to deconstruct not just modern reason but western “logocentrism” (and “phallocentrism”), while Leo Strauss took the path of restoring the intelligibility and credibility of the two premodern “roots of Western civilization,” Greek philosophy and Biblical religion. Closer to Derrida in deconstructing “all the way down,” Foucault, Merquior points out, eventually rediscovered the wisdom of norms and limits, precisely for critical and emancipatory projects to have their targets. Eros needs norms for its transgressive nature to be activated and active. The posthumously published History of Sexuality began this surprising turn. As we will see, however, theoretical-methodological decisions blocked his access to the original phenomena, that is, the masters of eros from Plato to Augustine. One doesn’t know whether to critique or pity Foucault. Probably both. While I have reservations about some of his readings, especially biblical, the Straussian Allan Bloom, in his study of Love and Friendship (1993), made a more good faith effort to understand the classical treatments of these fundamental human experiences.

During his career, Foucault was notorious on many counts, including his immediate defense of the “liberating” action of the Ayatollah Khomeini in taking over Iran and his famous claim that “man was dead” after the critique of modern reason. One could suspect the latter as being an overdrawn conclusion, however. For example, that the modern Cartesian subject, gloriously self-conscious and self-validating, was exposed as fiction and a fraud by genealogical demystification is not the same as destroying the reality or possibility of valid humanisms. The contemporary French philosopher Rémi Brague has made this case in more than one work (The Kingdom of Man; The Legitimacy of the Human). In general, any critique of the modern approaches to understanding the human, in Foucault’s very French case, “the human and social sciences,” does not touch other actual or potential approaches. They must be given an independent hearing. And while Descartes is a convenient symbol and target for those seeking to critique “modern thought,” other scholars such as Richard Kennington have dealt with him much more carefully and penetratingly than Foucault, who was still captive to distorting French pride and conventions. With Descartes, we have a test case for two sorts of historical or philosophical investigation, the “genealogical” and the effort “to understand a thinker as he understood himself.” We will return to this interpretive issue in a moment concerning Discipline and Punish. First, we must complete our brief survey of what we could call “the three faces” of Foucauldian reason.

Above, we alluded to his faulty practical judgment in politics, as evidenced by his enthusiastic welcoming of the ‘emancipatory’ Ayatollah Khomeini in Iran. To that, one could add his enthusiastic endorsement of Mao’s Cultural Revolution. Apropos of the first misguided endorsement, the young French political philosopher Pierre Manent conducted what later came to be known as a “fisking” of Foucault’s Iranian effusions. For those who read French, it is a wicked delight ("Lire Michel Foucault." Commentaire no. 7 (Autumn 1979): 369-75.). His personal life, too, which included unprotected gay sex in California bathhouses in the name of Nietzschean “limit-experiences,” provides important pieces of evidence of the character and quality of his thought, as he himself sought to embody and live it out. While not reducing a man’s thought to his sexuality as some do (see, for example, E. Michael Jones, Degenerate Moderns: Modernity as Rationalized Sexual Behavior), in Foucault’s case the linkage is undeniable and must be considered in assessing (not so much the person as) the thought. “Gay Nietzschean” is at once a paradox and a possibility for the emancipated deconstructive mind.

Politically and personally, therefore, there are grounds for being wary and indeed suspicious of Foucault’s intellectual judgment and the thought that undergirded it. In his study, Merquoir takes a critical scholarly look at the latter, including in a chapter devoted to Discipline and Punish entitled “Charting carceral society.” The key term in the title, “carceral,” immediately indicates its contemporary relevance and importance. One need only look at the deliberate pro-criminal malfeasance of Soros-funded prosecutors failing to uphold the law and unleashing criminality on property, businesses, and people. More generally, “the carceral state” is a long-standing descriptor adopted by left radicals bent on stigmatizing and overturning “white capitalist America” as systematically racist and unjust. Foucault’s Discipline and Punish provided major intellectual “heft” to this construct and agenda. He told “criminals” that their first duty in prison was to escape.

Merquior points out the house of cards upon which the purportedly scholarly analysis is built. On one hand, Foucault’s fundamental thought, that modern institutions are created by “discourses of power” for the sake of establishing “binaries of control,” presupposes or requires that there are “no facts of the matter,” that all such “facts” that are adduced are already prefabricated by a dominant discourse. On the other hand, Foucault uses – and must use – a full range of “facts” to make his case. Here is a contradiction that he could never overcome. As Foucault’s contemporary – and political and intellectual opposite – Raymond Aron said, “there are social facts.” If one wants a non-ideological model of the study of prisons, one could turn to another Frenchman, Alexis de Tocqueville, and his traveling companion Gustave de Beaumont and their study of the US penitentiary system. Or, in a more political science vein, the work of the late great James Q. Wilson continues to be a model. The tendentious character of Foucault’s approach clearly contrasts with these sober alternatives. While Foucault’s analysis may (or may not) have had some insights, its agenda-serving character means they are accidental or incidental and fundamentally questionable.

Petitiones Principii

Scruton, too, locates Foucault in the context of the currents and contests of post-war French intellectual life. Indeed, he pairs Foucault with Sartre in his chapter on “Liberation in France: Sartre and Foucault.” Sartre represents the “turn to existentialism” and “Marxism” by those dissatisfied with structuralism’s revolutionary potentials, while Foucault took the genealogical route. Scruton ventures two complementary statements of Foucault’s intention and complements Merquior’s exposé of the Achilles’ heels of his approach. Like most French intellectuals since Rousseau, Foucault “devoted his work to unmasking the bourgeoisie, showing that all the given ways of shaping civil society are reducible in the last analysis to forms of domination.” More generally,

[t]he unifying thread of Foucault’s earlier and most influential work is the search for the secret structures of power. Behind every practice, every institution and behind language itself lies power, and Foucault’s goal is to unmask that power and thereby to liberate its victims. When he was challenged, however, he is unable to encounter opposition without at once rising … to the superior ‘theoretical’ perspective, from which opposition is seen in terms of the interests that are advanced by it. Opposition relativized is also opposition discounted.

In this way, “his stance remains beyond the reach of every answer.” Petitio principii, indeed. The same point can be made in terms of his key concept of episteme – structures of ‘knowledge’ at the service of establishing and maintaining “power,”

Foucault … makes no clear contrast between episteme and some other, objective or explanatory form of ‘knowledge’. There seems to be no privileged position from which the episteme of an era is discernible that is not imbued by an episteme of its own. This raises the question – not, I think ever answered by Foucault – as to the method that would justify his observations, and whether or not he has obtained the impartial standpoint that would really entitle him to make them.

To this probing question, Scruton adds an observation concerning

the entirely unwarranted and ideologically inspired idea of dominance with which Foucault glosses his conclusions. He at once assumes that if there is power then it is exercised in interests of some dominant agent. Hence by sleight of hand, he is able to present any feature of social order – even the disposition to heal the sick – as a covert exercise of domination, which furthers the interests of those in power.

Speaking of modern natural scientists, Nietzsche said they put the bird (the scientific concept or law they want to find) in a bush, walk away, then come back and “discover” it. Scruton rightly recoiled before this a priori equation of all authority with “domination” or “authoritarianism.”

Anti-Bourgeois Ire

Returning to Foucault’s starting point, anti-bourgeois ire, Scruton notes that

it is possible to discern a persistent and simplifying historical perspective [in Foucault’s work]. Despite his apparent scholarship Foucault remains wedded to the mythopoetic guide to modern history presented in The Communist Manifesto. The world divides conveniently into the ‘classical’ and the ‘bourgeois’ eras, the first beginning in the late Renaissance and ending with the ‘bourgeois revolution’ of 1789. It is only thereafter that we witness the characteristic features of modern life: the nuclear family, transferable property, the legally constituted state, and the modern structures of influence and power.

One notes that Scruton, instead of employing the charged term “bourgeois,” benignly characterizes the elements of a decent society and political order in their modern iteration. No doubt, historically, the bourgeois order has had its excesses, its vanities, its shortfalls, and its oppressions – what social order hasn’t? But three centuries of “bourgeois-bashing” and the twin anti-bourgeois horrors of Nazism and Communism should give us pause. What have they wrought? What have they improved? What do they destroy? These days, when the common decencies aren’t very common, I suggest we look with a little more respect and even affection on this admittedly “mediocre” order. Aristotle said that a middle class society with elements of elevation was probably the best that most societies could hope for.

On the intellectual plane, I would venture that how a system of thought treats bourgeois society is a litmus test for its connection with human reality.

Paul Seaton, an independent scholar, is the translator of The Religion of Humanity (St. Augustine Press) and the author of Public Philosophy and Patriotism: Essays on the Declaration and Us (St. Augustine Press).

Politics

National Civitas Institute Poll: Americans are Anxious and Frustrated, Creating a Challenging Environment for Leaders

The poll reveals a deeply pessimistic American electorate, with a majority convinced the nation is on the wrong track.

.webp)

Liberal Democracy Reexamined: Leo Strauss on Alexis de Tocqueville

This article explores Leo Strauss’s thoughts on Alexis de Tocqueville in his 1954 “Natural Right” course transcript.

%20(1).avif)

Long Distance Migration as a Two-Step Sorting Process: The Resettlement of Californians in Texas

Here we press the question of whether the well-documented stream of migrants relocating from California to Texas has been sufficient to alter the political complexion of the destination state.

%20(3).avif)

Who's That Knocking? A Study of the Strategic Choices Facing Large-Scale Grassroots Canvassing Efforts

Although there is a consensus that personalized forms of campaign outreach are more likely to be effective at either mobilizing or even persuading voters, there remains uncertainty about how campaigns should implement get-out-the-vote (GOTV) programs, especially at a truly expansive scale.

There's a Perception Gap With the U.S. Economy

As we approach another election cycle, it’s worth asking: what’s real, what’s political theater, and what does it all mean if Democrats regain control of the House?

International Law Is Holding Democracies Back

The United States should use this moment to argue for a different approach to the rules of war.

Trump purged America’s Leftist toxins. Now hubris will be his downfall

From ending DEI madness and net zero to securing the border, he’ll leave the US stronger. But his excesses are inciting a Left-wing backlash

California’s wealth tax tests the limits of progressive politics

Until the country finds a way to convince the average American that extreme wealth does not come at their expense, both the oligarchs and the heavily Democratic professional classes risk experiencing serious tax raids unseen for decades.

When Duvall Played Stalin

It’s strange to compliment an actor for impersonating a tyrant, but it is an act of courage.

When Vanity Leads to Impropriety

A president should simply not be allowed to name anything after himself without checks from Congress or an independent commission.